Imagine this scenario. You’re walking down the aisle of a supermarket pushing a shopping trolley. As you round the corner into the next aisle you encounter a fellow shopper about to exit the aisle you’re entering. A trolley collision is narrowly avoided but only when the other shopper quickly changes direction.

What’s your first instinct?

If you said you’d offer a quick sorry you’re not on your own.

In these situations it’s common to offer a quick sorry. But why is it that these apologies seem to come more often from women than men?

It occurred to me recently that saying sorry when sorry isn’t warranted brings no good to the cause of women’s rights. I was becoming annoyed at women who said sorry for what I considered to be inconsequential shopping trolley incidents.

The truth is I saw their sorries as a sign of women subverting their own interests, deferring their needs and being unwilling to claim their own space much less what it is they wanted.

And I’m not on my own in seeing sorries from women in this way.

On Jezebel, writer Karen Polewaczyk sparked controversy with her ideas about why women say sorry “all the time”. In her view, saying sorry is a result of women feeling the weight of unhealthy societal expectations and expressing themselves in a self-deferential manner:

I think it’s that women are expected to be exceptionally grateful for the crumbs tossed our way—and so we show our gratitude by cushioning our wants with a series of, “I know this is asking a lot, but…”, “I hate to ask, but could you…” and “I might sound like an idiot for wondering, but…”-isms.

I share Polewaczyk’s sensibility. Or at least I did.

I share Polewaczyk’s sensibility. Or at least I did.

It’s not that I don’t apologise or appreciate receiving an apology. Saying a genuine sorry plays an important part in building and maintaining relationships. Apologies smooth ruffled feathers and calm volatile situations. At times an apology is the only way to achieve reconciliation and get strained relationships back on track.

But saying sorry for the sake of it is demeaning and, until recently, I wanted women to say sorry less!

Driving to the office one afternoon I was listening to talkback radio. It was the usual ABC afternoon fare, nothing too heavy…then they asked: When should you say sorry?

I fired straight up. This was my opportunity to save women from themselves, to set them straight, to tell them to stop saying sorry. I called and voiced my opinion and was immediately met with opposition, especially from the female DJ. Her view was that her saying sorry didn’t mean that she was being any less of a person. Possibly, she conceded, saying sorry too often diminished the value of the word but it definitely didn’t mean that she was being subservient or in any way feeling guilty for her existence.

I was undaunted. I had truth on my side…or at least that’s what I thought.

On returning to the office I mentioned my phone conversation to my colleague Emily Murphy. Emily is a deeply committed humanitarian and feminist who has a powerful moral compass. Her sense of fairness and equanimity runs deep.

“Why can’t women see this?” I asked with passion.

Not one to shirk an issue, Emily quickly pointed out that my claims weren’t supported by empirical evidence. “True,” I countered, “but I’m sure I’m right.” Then she retorted, “You’re just trying to get women to behave the same as men!”

That wasn’t the way I saw it. Not by a long shot. But sometimes the things that sting the most do so because they have truth on their side.

Suspecting my hypothesis was on shaky ground I decided to conduct some research. As I was to be in Bali the following weekend I resolved to observe all of the times someone said sorry to me. I figured that Bali was the perfect place. There would be plenty of Aussies navigating rough, hazardous sidewalks so there’d be lots of unexpected encounters that could give rise to a quick ‘sorry’.

I wasn’t disappointed. Over the course of the weekend people said sorry on several occasions and the number of sorries were about even from males and females.

My thesis was shakier than a Balinese footpath. I needed more and better quality research.

Turning to Facebook, I asked: “I’m writing an article about gender-based stereotypes and I’m interested in your response to this question: Who apologises the most, men or women?” As of this writing it generated 36 comments from 30 different contributors.

The comments ranged from those who believed women apologised more,

If I was a betting woman I would say Women

Women I know I do sometimes for no reason

Woman because I think overall we are more conscious of other people’s feelings towards us.

to those who said it was men,

I think men. We tend to overlook more small stuff.

and to those who believed behviour wasn’t gender specific and required a more fullsome explanation.

t’s not gender specific Peter.

My understanding of it is that in general, women and men view apologies differenty (and Noms – personality traits/tools are as much a generalisation as gender traits so we can’t take either as “truth”). Women typically view apologies as a gesture of “empathy” and will apologise even if they’re not in the wrong – as in “I’m sorry that you feel …” whereas men see it as an admission of guilt and are therefore less likely to apologise – but again, these are generalisations…

woman i reckon… but then its difficult to say…my man likes to appologise a fair bit as well

Clearly my research was far from conclusive so I went chasing articles about the subject.

It turns out that my initial thoughts reflect commonly held understandings about human behaviour based on gender stereotypes. In other words, a lot of people believe that women apologise more than men.

And they’re right!

According to research conducted on Canadian university students [PDF download, 693KB] women do apologise more than men.

The research asked 66 participants (33 male, 33 female) to each maintain an apology diary. Each diary was in two sections. The first was the “transgressor” section where participants noted instances during the day where they either apologised to someone or did something that they thought warranted an apology. The “victim” section contained entries that described moments where someone else either apologised to or did something that warranted an apology to the participant.

Analysis of these diary entries produced clear evidence that the female participants in the study apologised more than their male counterparts. However, the analysis also showed that women reported committing more apology-worthy offences than men. As a percentage of offences committed, though, there was no difference between males and females — both reported apologising on approximately 81% of the occasions in which they committed an offence.

In other words, “once men and women categorized a behavior as offensive, they were equally likely to apologize for it, and their apologies were similarly effusive.” (p. 3)

The study further noted that men reported fewer occasions of being the victim of an offense than women.

Thinking back to the supermarket example, as a male I’m statistically less likely than a woman to apologise for a shopping trolley incident. But I’m also less likely to expect an apology if I was the victim in the same incident.

In other words, women have a “lower threshold for what constitutes offensive behavior…[and] are more likely than men to judge offenses as meriting an apology.” (p. 3) So it should come as no surprise that some women offer an apology about a shopping trolley incident when my first instinct is to not even notice the incident.

But why is this the case?

According to the authors, there are two possibilities. First, women tend to be more relationship focussed and invest themselves in maintaining harmony through being aware of the the feelings of others. Second, “men have a higher threshold for both physical and social pain.” (p. 6) As both forms of pain arise from similar psychological mechanisms, they say, males are more likely to be ambivalent to the social pain that a woman might consider warrants an apology.

The bottom line? “Men and women unwittingly disagree at an earlier stage in the process: identifying whether or not a transgression has even occurred.”

What have I learned from this?

There are a number of valuable lessons that arise out of these observations

- There are differences in what men and women consider warrants an apology. These differences indicate neither superiority or weakness. Rather they point to different ways that males and females deal with personal interactions.

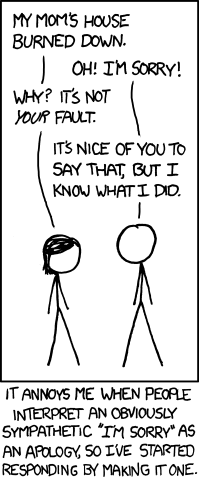

- The word sorry doesn’t always convey regret or guilt. It can be simply an oops or an acknowledgement of another’s pain. In short it’s a helpful social lubricant.

- Making assumptions about what’s in the mind of another isn’t helpful. Rather, assumptions reinforce stereotypes, prejudices and differences. Differences create wars. No-one wants war.

- If gender is a performance then neither performance is better than another. To live a life of intention it’s important to own all of our performance and not defer to some male/female ‘instinct’. If we look closely enough that instinct doesn’t exist.